Reflections From the 4th Reproductive Aging Conference

A debrief on the annual meeting of a growing scientific community around ovarian aging and longevity.

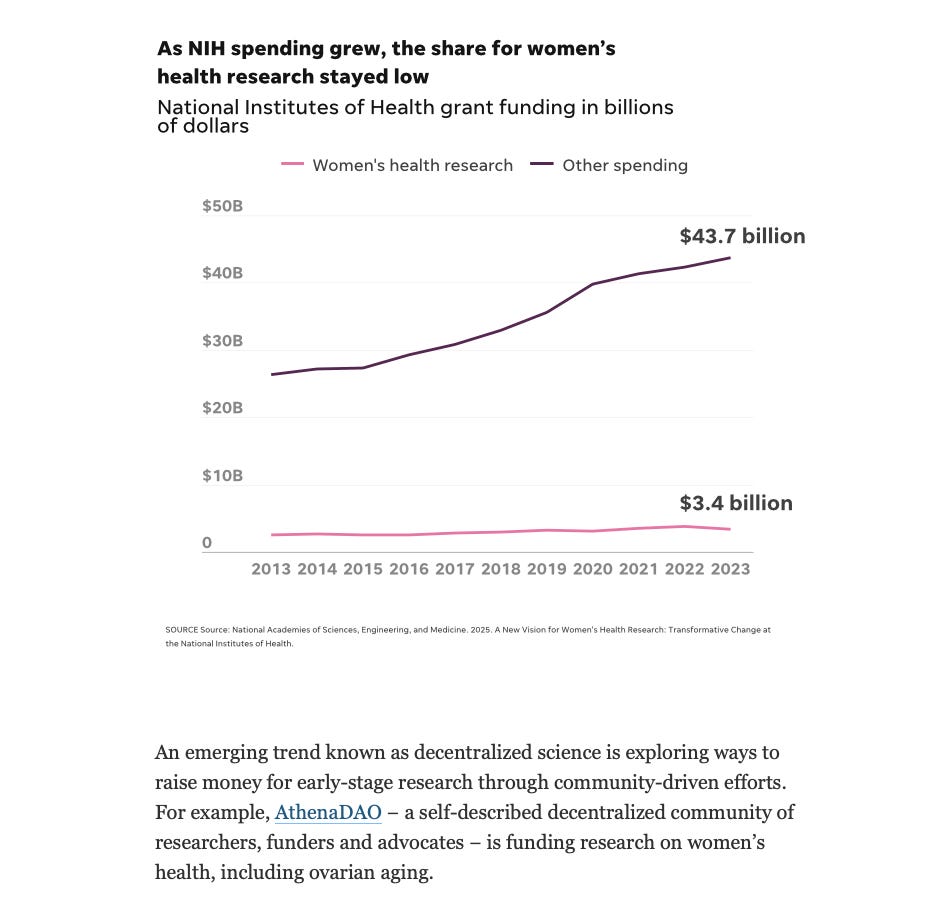

🗞️AthenaDAO on USA Today!

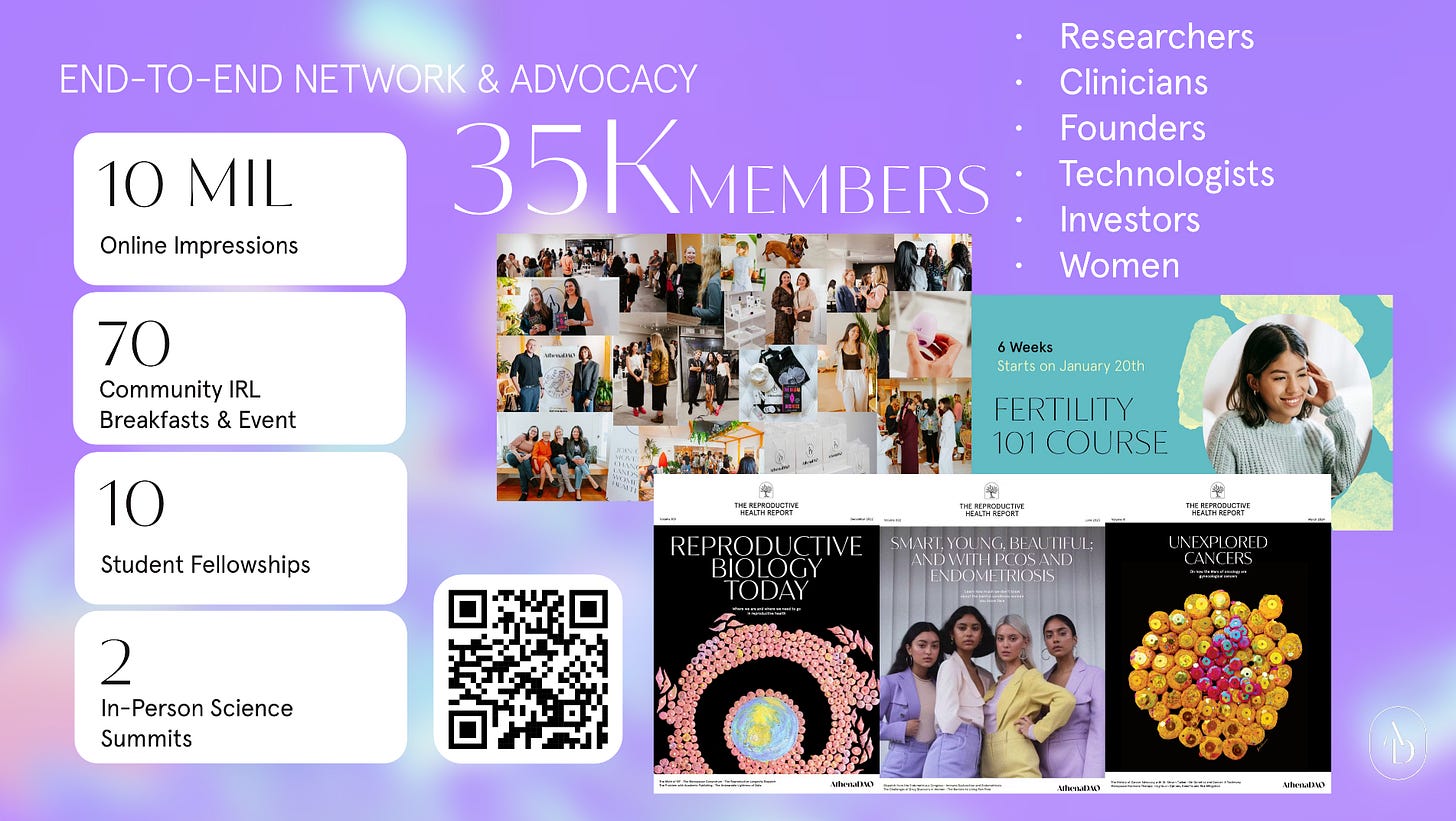

AthenaDAO’s work funding women’s health research mentioned in an ovarian health article on USA Today is a great way to celebrate our upcoming third year anniversary this August.

It is also a great opportunity to say we are grateful and thankful to everyone who has supported us; from our contributors, funders, researchers, clinicians, advocates, and women who are part of our global community.

Thank you to leaders in their fields like Dr. Jennifer Garrison, Dr. Bérénice Benayoun, and Dr. Lizellen La Follette, and so many more who say yes to our initiatives highlighting the importance of “science first”.

We are coming to a massive inflection point in women’s health and we are excited that AthenaDAO is ready and also evolving for this moment (our Demo Day showcased this). More over, we are thrilled that so many organizations are now following in our footsteps replicating our model. The more capital there is for women’s health R&D, the better it is for all women.

For AthenaDAO, it will always be about transformative women’s health research, education, and access! 🧬🪩

Reflections From the 4th Reproductive Aging Conference

By Dr. Skye Glenn, AthenaDAO Science and Deal Flow Contributor.

In May, Dr. Skye Glenn attended the 4th annual Reproductive Aging Conference in San Jose, California, USA.

A field coming into its own.

The study of ovarian function is simultaneously a very old and very new field. It’s very old in the sense that doctors have been performing procedures like ovarian grafting as early as the 19th century, but young it that we are only now starting to understand the ovaries for what they are–not simply a reproductive organ, but a complex focal point of the endocrine system, important to nearly every aspect of female health.

At the opening session of this year’s Reproductive Aging Conference, organizer Dr. Jennifer Garrison announced that she, along with co-organizers Drs. Yousin Suh and Francesca Duncan, are considering changing the name of the conference to reflect this shift in understanding.

This is an attitude that pervades the conference – an energy of iteration, the excitement of building something new. As one postdoc put it to me, ovarian aging as an organized field of research is so new that everyone is coming from a different scientific background and applying the skills they have developed elsewhere. There are no incumbents, “we’re just figuring it out together.”

Over the four days of talks, workshops, and poster sessions, I got a sense for a field actively laying its foundation, having to answer basic questions and build fundamental tools neglected by science–until now.

Biomarkers are the first big tool to tackle.

During a workshop, participants gathered into about ten groups to identify the most pressing, complex topics in ovarian research for an upcoming XPRIZE competition. Every single group converged on the same conclusion: we need more and better biomarkers for ovarian aging over the complete reproductive lifespan.

Biomarkers are measurable indicators of a biologic state – think, blood pressure as an indicator of cardiovascular health, or detecting white blood cells in a urine sample pointing to a urinary tract infection. Biomarkers are essential in the clinic to establish an individual’s baseline, identify deviations, select therapeutics, and monitor treatment efficacy. Biomarkers are also vital in the lab to study the system in question.

There are a few long-standing biomarkers that indicate ovarian status, like AMH and FSH, which report on the quantity of eggs in the ovarian reserve. However, as clinicians in the audience remarked, they are imperfect, particularly in people with conditions like PCOS, and they tell us nothing about the quality of existing eggs. Without accurate biomarkers and an understanding of their variability across individuals, we can’t understand–and ultimately, preserve–the ovarian reserve if we don’t have reliable ways to measure it.

The lab of Dr. Kathryn Grive from Brown University is working on one such biomarker called Ubiquitin C-Hydrolase L1, or UCHL1. Human ovaries contain all the eggs a female will have in her reproductive life when she is born, a “fixed reserve.” Consequently, eggs are incredibly long-lived cells; while skin cells turn over every month, an egg can last over 40 years. As such, they reasoned that such cells must have excellent mechanisms for intracellular maintenance. Enter UCHL1, a regulator that helps maintain healthy proteins in proper abundance in the oocyte.

Dr. Grive’s team found that UCHL1 is highly enriched in oocytes during fetal development, suggesting preparation for long-term cellular maintenance, and offering the first clue that it could serve as a biomarker of egg quality. They observed higher levels of UCHL1 in blood serum in female mice and humans compared to males, as well as lower levels in mouse models of diminished ovarian reserve. Because of its role in aging, there is excitement that UCHL1 could inform clinicians about the quality of the eggs in the ovarian reserve, in addition to the quantity.

Biomarkers need not be molecular in nature, like UCHL1. Biomechanics also offer clues, as it’s well known that ovaries become fibrotic and stiffen as they age. Dr. Elnur Babayev from Northwestern University is using a form of ultrasound called shear wave elastography to measure the tissue stiffness of ovaries in the body. With promising results showing that maximum stiffness increases with reproductive age, ongoing studies in his lab are investigating the relationship between these stiffness metrics and IVF outcomes.

Drs. Grive and Babayev are not alone in this quest for biomarkers. Dr. Zhongwei Huang from National University Singapore is exploring how microRNA expression profiling coupled with machine learning can accurately predict oocyte quality. Dr. Vittorio Sebastiano made a plug for the Biomarkers of Aging Consortium, which will be hosting its own conference in October.

In order to study women, we need to build the tools that allow us to answer questions. We have a long way to go, but these pioneers are paving the way.

From the bench to the bedside, and back again.

In addition to biomarkers, there were fascinating talks on a range of topics, from the most basic cell biology to potential therapeutics. Once such talk was by Dr. Rebecca Robker from the University of Adelaide, who studies telomeres, the protective caps at the ends of our DNA that shorten as we age. The longer the telomeres, the better. Babies conceived using IVF or to mothers of advanced maternal age have shorter telomeres on average, due in part to mitochondrial stress. Dr. Robker’s team showed that simply treating mice with mitochondria-enhancing small molecules like BGP-15 and MitoQ recovered telomere length in embryos after mitochondrial stress.

As people choose to have children later in life and the use of IVF increases, this represents an exciting possibility to recover telomere length and offset the downsides of waiting to conceive. But how do we get from here–from mice drinking MitoQ in a lab–to bettering life and expanding reproductive options for people? Fortunately, there were several medical doctors participating in RAC, and bridging the gap between bench scientists and clinicians at the bedside was a major theme of the conference.

Dr. Kara Goldman from Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine spoke to this widening gap. As an example, she noted that the typical reproductive endocrinology fellowship has shifted from a required 18 months of research to being exclusively clinical. In her estimation, this had led to less crosstalk between scientists and clinicians, as well as erosion of literacy in basic science for doctors. Many are trying to correct this rift. Dr. Stephanie Faubion, the Medical Director of The Menopause Society, was in attendance. She informed us that two of the goals in their Mission Statement are to support research in menopause and distribute information and continued professional education to healthcare providers, forming a bridge between the two.

While we typically think of research as feeding into the clinic, the relationship goes both ways. Dr. Veronica Lobo-Gomez took the opportunity to notify the audience about the Oncofertility Ovarian Tissue Slide Image Databank. The human ovaries represent a fixed reserve and collection of the tissue is invasive, making it an ethically non-viable tissue for researchers to study in most cases. Dr. Lobo-Gomez works to preserve fertility in children diagnosed with cancer, and she found a way to work with this limitation. By forming an agreement with patients, she collected a small sample from her fertility preservation cases, assembling an unprecedented repository of precious samples now available to researchers.

My take-away: this is why we’re here. We are human and, as a result, our systems of information sharing and collaboration are inherently imperfect. But we have come together for these four days for this very purpose–letting each other know what we’re up to, what we have to offer, what questions we’re trying to answer–so that we can build toward the future we’re envisioning together.

Optimism for reproductive aging research in the new fiscal reality.

The current state of research funding by the American government was, inevitably, the backdrop on which this entire conference took place. The US National Institute of Health (NIH) is–by a wide margin–the biggest funder of biomedical research in the world. However, to date, around $9.5 billion in NIH funding has been canceled for 2025.

Not one person involved with RAC 2025 was untouched by the chaos in Washington, whether because they had lost funding, or hadn’t been able to attend the conference at all due to uncertainty over being let into the US. I talked to more than one postdoc who chose to come to this particular conference because of the timing–they needed to use their NIH grant before it was taken back by the government.

Despite the turmoil, organizer Dr. Yousin Suh offered cautious optimism. While DOGE has threatened to reduce the NIH budget by 40%, Dr. Suh pointed out that the National Institute on Aging (NIA), a division of the NIH, has not seen any major cuts. The ovaries are the fastest-aging human organ, and their function influences the healthspan of the entire female body and a whole host of age-associated diseases (e.g., Alzheimer’s Disease, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis). As such, ovarian research is often grouped under the umbrella of aging and longevity research. Oddly, this categorization may offer protection to the field.

Attendees noted that the current administration’s fixation on pronatalism may be another strange bedfellow to the reproductive aging field. Regardless of the optimism, participants recognized that scientists will increasingly rely on private funding in the future. Amongst the postdocs, I encountered a sentiment that the US may no longer be the future of research, with many of them considering Europe for their future lab groups.

While it’s too early to say where or how the reproductive aging field will go, there is a sense that it’s here to stay. While today’s leaders come from many different backgrounds, there is also energy and determination among the young mentees who are being raised in these waters. I sensed an ease in taking up space, a self-assured knowing what they are dedicating their lives to matters. It gives me confidence this field will not only survive, but thrive, even–maybe especially–in a hostile environment.

Read the latest paper on the field: Studying ovarian aging and its health impacts: modern tools and approaches.

👩🔬 Looking to support research? Or projects to join?

AthenaDAO is currently helping incubate a variety of studies!

Feel free to join any of the following:

Join AthenaDAO and CoopHive in building the first reproductive longevity AI agent

Learn more about ProFaM and it’s ovarian tissue cryopreservation

Learn more about Gero.AI and our project with them

Learn about our Fertility Acceleration project investigating diminished ovarian reserve through the cGAS-STING pathway